Pavel Curtis in conversation with Judy Malloy, 1993. Recorded in Dealers of lightning: Xerox PARC and the dawn of the computer age

Pavel Curtis in conversation with Judy Malloy, 1993. Recorded in Dealers of lightning: Xerox PARC and the dawn of the computer age

"The study of cybertexts reveals the misprision of the spacio-dynamic metaphors of narrative theory, because ergodic literature incarnates these models in a way linear text narratives do not.... The cybertext reader is a player, a gambler; the cybertext is a game-world or world-game; it is possible to explore, get lost, and discover secret paths in these texts, not metaphorically, but through the topological structures of the textual machinery."

Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature by Espen J. Aarseth, 1997

"Virtual communities, including MOOs, are amalgamations of technological interfaces, computer programming, and 'real' bodies. This monstruous body, a space of fragmentation, confusion and alternative realities, promises or threatens to destabilize the embodied experience as we know it. Those who build and write their bodies in Cyberspace can see how they participate in constructing bodies in their local community... the corporeal entity that we think of as our 'body' is more contingent, fragmentary, and elusive than we may have previously expected."

Cabinet of Curiosity: Finding the Viewer in a Virtual Museum by Michele White, 1997"More than most other traditional ways of representing the world, maps conjure a vision of

representation itself as a space the viewer might enter into bodily, a construct not

merely to be comprehended but to be navigated as well. They invite interaction, and

of course they frustrate it too: their smooth surfaces remain impenetrable, like shop

windows, inspiring in the most avid map-gazers a yearning that has less to do

perhaps with simple wanderlust than with an ancient dream of literal travel into the

regions of the figurative."

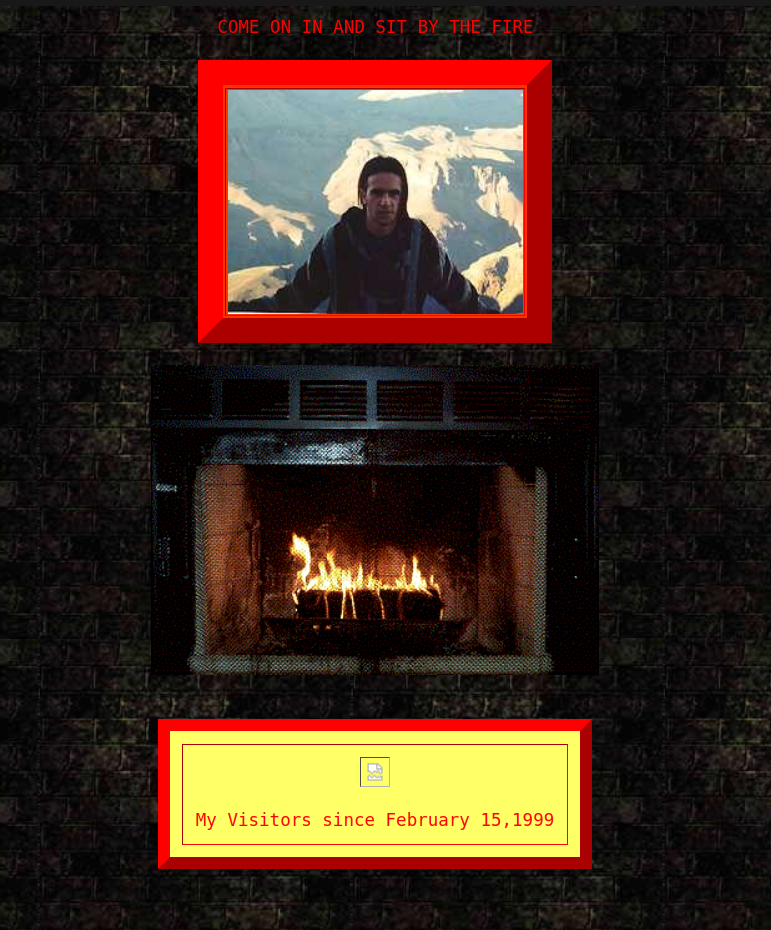

My Tiny Life: Crime and Passion in a Virtual World by Julian Dibbell, 1999 A personal homepage on geocities in the West Hollywood neighborhood.

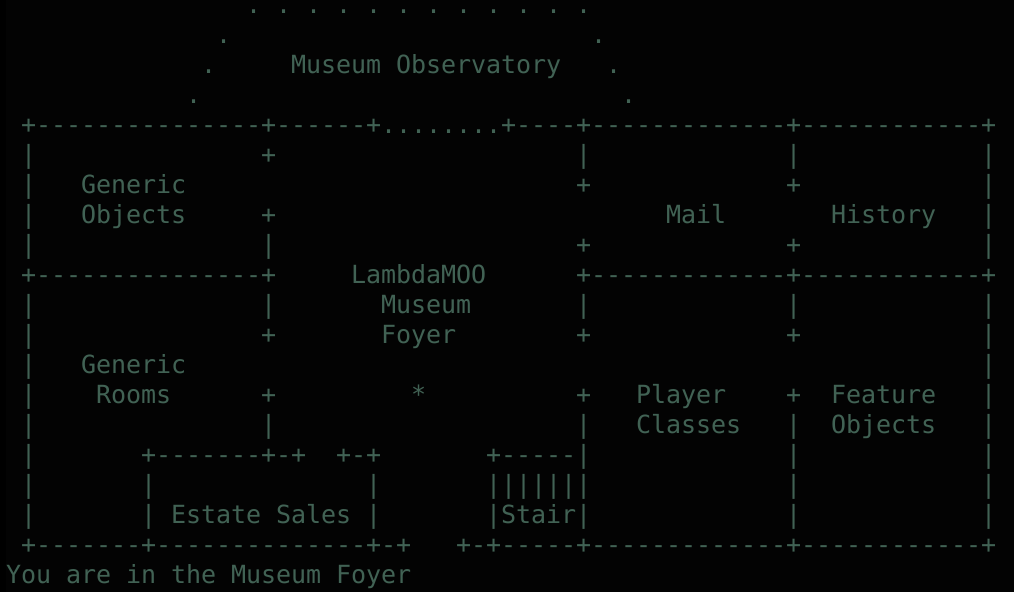

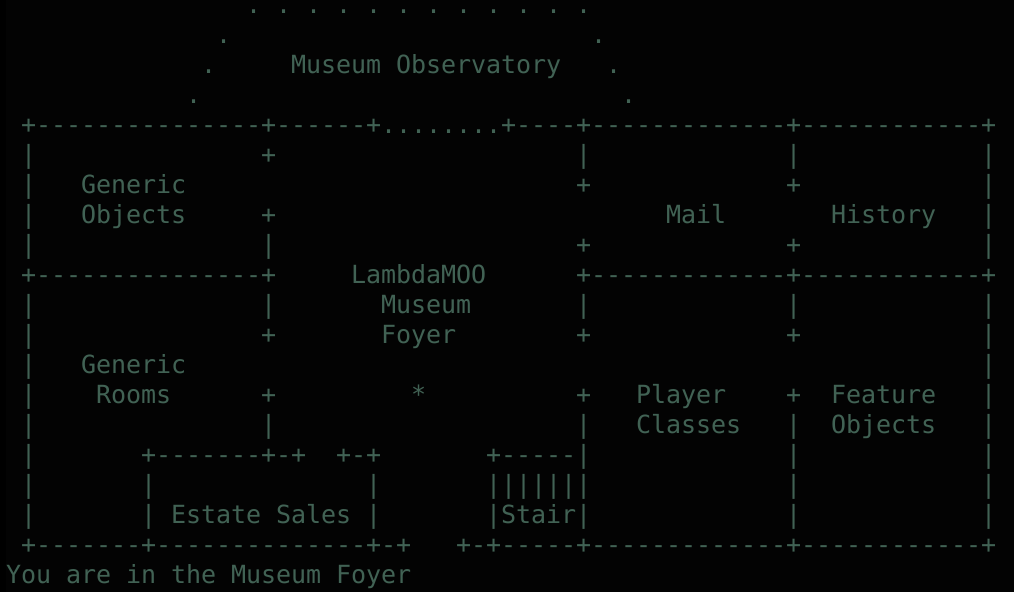

A personal homepage on geocities in the West Hollywood neighborhood.  Map of LambdaMOO museum

Map of LambdaMOO museum Map of Neopia, the virtual world of Neopets

Map of Neopia, the virtual world of Neopets"Rigid hypertext is streetscape and corporate office: simple, orderly, unsurprising. We may find the scale impressive, we admire the richness of materials, but we soon tire of the repetitive view. We enter to get something we need: once our task is done we are unlikely to linger... Gardens and parks lie between farmland and wilderness. The garden is farmland that delights the senses, designed for delight rather than commodity. The park is wilderness, tamed for our enjoyment. Since most hypertext aims neither for the wilderness of unplanned content, nor for the straight rows of formal organization, gardens and parks can inspire a new approach to hypertext design and can help us understand the patterns we observe in fine hypertext writing."

Hypertext Gardens by Mark Bernstein, 1998"the slowly loading pages of old, accompanied by the funky buzz of the modem, had their own weird poetics, opening new spaces for play and interpretation... Meanwhile, Google, in its quest to organize all of the world’s information, is making it unnecessary to visit individual Web sites in much the same way that the Sears catalog made it unnecessary to visit physical stores several generations earlier.... the whole point of the flâneur’s wanderings is that he does not know what he cares about. As the German writer Franz Hessel, an occasional collaborator with Walter Benjamin, put it, “in order to engage in flânerie, one must not have anything too definite in mind.” "

The Death of the Cyberflâneur by Evgeny Morozov, 2012 "The Garden of Forking Paths is a picture, incomplete yet not false, of the universe such as Ts'ui Pen conceived it to be. Differing from Newton and Schopenhauer, your ancestor did not think of time as absolute and uniform. He believed in an infinite series of times, in a dizzily growing, ever spreading network of diverging, converging and parallel times. This web of time - the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect or ignore each other through the centuries - embraces every possibility.” "

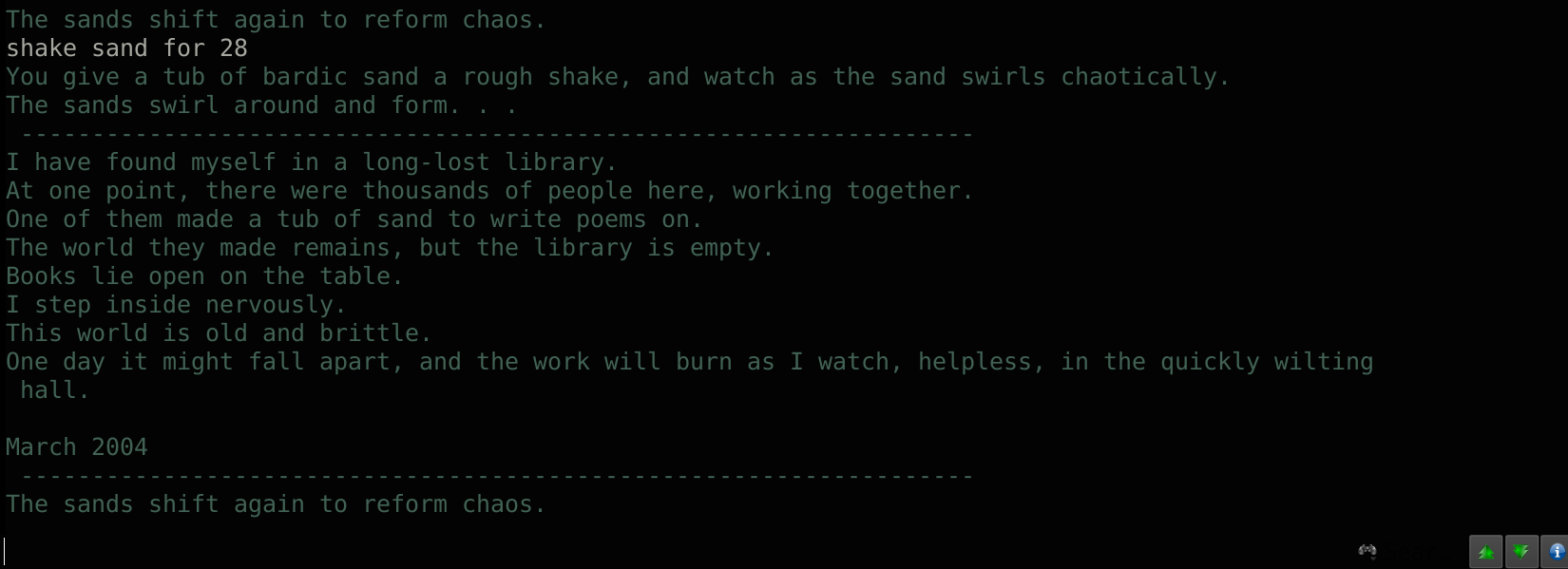

The Garden of Forking Paths by Jorge Luis Borges, 1941  Poem recorded in the tub of bardic sand in the LambdaMOO Library

Poem recorded in the tub of bardic sand in the LambdaMOO Library

"Xanadu, the ultimate hypertext information system, began as Ted Nelson's quest for personal liberation.. He wanted to be a writer and a filmmaker, but he needed a way to avoid getting lost in the frantic multiplication of associations his brain produced. His great inspiration was to imagine a computer program that could keep track of all the divergent paths of his thinking and writing. To this concept of branching, nonlinear writing, Nelson gave the name hypertext."

The Curse of Xanadu by Gary Wolf, Wired Magazine, 1995"In a world where algorithms guard against experiences that don’t fit our past preferences, some of us yearn for the delights of getting lost. Disorientation is the equivalent, in space and time, of the visual defamiliarization that was the 20th-century avant-garde’s job description. Yet the code behind our online lives is designed to thwart disorientation.... The flâneur regards the world with a camera eye, as Susan Sontag notes in On Photography: “The voyeuristic stroller ... discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes. Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, he finds the world ‘picturesque.’”

Mourning eBay’s Days as the Internet’s Kitschiest, Most Surreal Mall by John Dery, 2017"The programming of the museum space brings the viewer to confront an architectural order. The unbounded spaces of the linked, but not insistently proximal, virtual environment are cohered into a traversable plan by the museum. This plan would appear to regulate the body of the viewer in a way that evokes the traditional museum’s practice of ordering the visitor’s movement, standardising social routines, and reforming manners. The programming in the foyer enforces boundaries. It is through this regulation that a defined and mannered virtual viewer may be described... The enforcement of boundaries within the museum operates by a different principle than the architecturally partitioned spaces of the material world. In the MOO museum, boundaries can’t be justified by the physical limits that a space exacts on the viewer’s body. The restrictions to the body that are ordinarily imposed by facade, steps, curbs, floors, walls, and furniture are disabled by the virtual environment, even if textual descriptions of these markers remain. Materially built space is made into a container and contextually demarcated by the architectural brackets of face and facade. In the MOO environment, boundary is not linked to face or facade by any architectural vernacular. Virtual rooms are usually conceived of as a set of interiors. They are not defined by a facade vocabulary of doors, exterior walls, and entrances. ’Face’ and ’facade’ may not be part of the same structure inside of MOOs. The facade of LambdaMOO and indeed the facade of all MOOs may be a log-on screen. This welcoming text presents a door onto the MOO space rather than a presentation of the city or community environment."

Cabinet of Curiosity: Finding the Viewer in a Virtual Museum by Michele White, 1997

Talking about the “reality” behind a software system is deceptive for at least four reasons. First, reality is in the eyes of the beholder... Second, the notion of real world collapses in the not infrequent case of software that solves software problems — reflexive applications, as they are sometimes called. Take a C compiler written in Pascal. The “real” objects that it processes are C programs. Why should we consider these programs more real than the compiler itself?.. The third reason is a generalization of the second. In the early days of computers, it may have been legitimate to think of software systems as being superimposed on a pre-existing, independent reality. But today the computers and their software are more and

more a part of that reality. Like a quantum physicist finding himself unable to separate the measure from the measurement, we can seldom treat “the real world” and “the software” as independent entities... To describe the operations of a modern bank is to describe mechanisms of which software is a fundamental component. The same is true of most other application areas; many of the activities of physicists and other natural scientists, for example, rely on computers and software not as auxiliary tools but as a fundamental part of the operational process. One may reflect here about the expression “virtual reality”, and its implication that what software produces is no less real than what comes from the outside world... The last reason is even more fundamental. A software system is not a model of reality; it is at best a model of a model of some part of some reality... The general theme of the object-oriented method, abstract data types, helps understand why we do not need to delude ourselves with the flattering but illusory notion that we deal with the real world. The first step to object orientation, as expressed by the ADT theory, is to toss out reality in favor of something less grandiose but more palatable: a set of abstractions characterized by the operations available to clients, and their formal properties... Never do we make any pretense that these are the only possible operations and properties: we choose the ones that serve our purposes of the moment, and reject the others. To model is to discard.To a software system, the reality that it addresses is, at best, a cousin twice removed."

Object Oriented Software Construction (Second Edition) by Bertrand Meyer, 1997

A computer screen showing a background wallpaper photo of the Palace of Versailles, 2005. Found on Wallpaper (computing) wikipedia article.

A computer screen showing a background wallpaper photo of the Palace of Versailles, 2005. Found on Wallpaper (computing) wikipedia article. Screenshot from The Sims 1, unknown source

Screenshot from The Sims 1, unknown source